Angular diameter distance

The angular diameter distance is a distance measure used in astronomy. The angular diameter distance to an object is defined in terms of the object's actual size,  , and

, and  the angular size of the object as viewed from earth.

the angular size of the object as viewed from earth.

The angular diameter distance depends on the assumed cosmology of the universe. The angular diameter distance to an object at redshift,  , is expressed in terms of the comoving distance,

, is expressed in terms of the comoving distance,  as:

as:

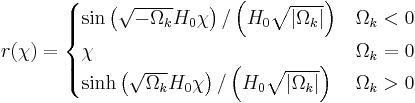

Where  is defined as:

is defined as:

Where  is the curvature density and

is the curvature density and  is the value of the Hubble parameter today.

is the value of the Hubble parameter today.

In the currently favoured geometric model of our Universe, the "angular diameter distance" of an object is a good approximation to the "real distance", i.e. the proper distance when the light left the object. Note that beyond a certain redshift, the angular diameter distance gets smaller with increasing redshift. In other words an object "behind" another of the same size, beyond a certain redshift (roughly z=1.5), appears larger on the sky, and would therefore have a smaller "angular diameter distance".

Contents |

Angular size redshift relation

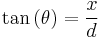

The angular size redshift relation describes the relation between the angular size observed on the sky of an object of given physical size, and the objects redshift from Earth (which is related to its distance,  , from Earth). In a Euclidean geometry the relation between size on the sky and distance from Earth would simply be given by the equation:

, from Earth). In a Euclidean geometry the relation between size on the sky and distance from Earth would simply be given by the equation:

where  is the angular size of the object on the sky,

is the angular size of the object on the sky,  is the size of the object and

is the size of the object and  is the distance to the object. Where

is the distance to the object. Where  is small this approximates to:

is small this approximates to:

.

.

However, in the currently favoured geometric model of our Universe, the relation is more complicated. In this model, objects at redshifts greater than about 1.5 appear larger on the sky with increasing redshift.

This is related to the angular diameter distance, which is the distance an object is calculated to be at from  and

and  , assuming the Universe is Euclidean.

, assuming the Universe is Euclidean.

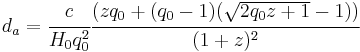

The actual relation between the angular-diameter distance,  , and redshift is given below.

, and redshift is given below.  is called the deceleration parameter and measures the deceleration of the expansion rate of the Universe; in the simplest models,

is called the deceleration parameter and measures the deceleration of the expansion rate of the Universe; in the simplest models,  corresponds to the case where the Universe will expand for ever,

corresponds to the case where the Universe will expand for ever,  to closed models which will ultimately stop expanding and contract

to closed models which will ultimately stop expanding and contract  corresponds to the critical case – Universes which will just be able to expand to infinity without re-contracting.

corresponds to the critical case – Universes which will just be able to expand to infinity without re-contracting.

The Mattig relation yields the angular-diameter distance as a function of redshift for a universe with ΩΛ = 0.[1]

References

- ^ An introduction to the science of cosmology, Chapter 6:2 by Derek J. Raine & Edwin George Thomas (2001)